Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 21

Repetition and variation (3/3)

Like great explorers, we now equip the stage like we would equip a ship for a long journey. We have maps on board, the whole crew is here, we have to prepare and coordinate manoeuvres so we can be ready to confront the unknown.

We must prepare the body, repeat and rehearse movements so that every moment of the performance can be nourished by symbiosis, that necessary quality that gives the whole piece a magical dimension.

However, we must be really patient when we learn these gestures: they require a total re-education of the body. Each body is marked by its own habits, the way it breathes, its history. We must allow the body to find its own points of reference, its own breaking points, so that the most unusual of movement can become the most spontaneous.

How to work with this “arm … [that] Is, like a blasted sapling, wither'd up”? How can we ensure each gesture can express what is at stake in each moment? How can we tune our breathing pattern to each character’s? Like an artisan who, repeating it a thousand times, eventually manages to do very naturally the most complex of gestures, we craft our body.

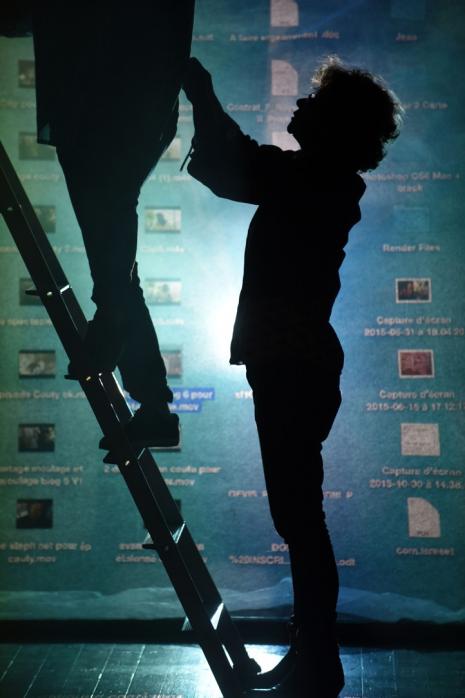

The many characters Élodie Bordas has to play mean a multitude of personalities: subtle variations of their voice or in the way they speak, as well as in their bodies and the way they move. Jean Lambert-wild’s clown, on the other hand, has to work on Richard III’s character with all the subterfuges that this implies. They both rigorously rehearse these gestures, ad infinitum, to the point where repetition itself transforms their bodies. They then acquire strange reflexes that adjust their energy to the stakes of their performance.

With movement comes the question of how scenes succeed to one another. We have to create the illusion that an actor who has disappeared in one place can instantly reappear in the body of another character. We have to ensure these appearances and disappearances don’t prevent the actor from going into the scene that follows with an even stronger increase of energy. We have to work on our breathing so that we don’t inadequately become short of breath, and so we can intelligently redistribute our energy to make sure each scene is filled with as much intensity of focus as possible. We also need to have the necessary endurance that a two-hour long performance, carried by two actors, requires

Rehearsing movement is not just the actor’s rehearsal: it is the entire ship that must go to sea, the whole crew is involved in this manoeuvre. Pace and time must fit and we must know how to combine them in every circumstance.

This is why the stage manager’s gestures are essential: every movement of the set, every time the curtains open, every costume change, lighting cue, music note must be in tune with what is being performed, must find the rhythm of the whole, the warmth of its intensity, the breath of a colour, the depth of a material. To do so, the crew must trial, and fail, and try again until we are all in tune in what it is that unites us.

Because once the ship is at sea – similarly to how, once it has started, it is not possible to backtrack a performance – the crew’s automatisms are essential. They allow us to face the open sea: the audience, the different venues, the actors’ little depressions, the technical issues, the moments we forget our lines, sea sprays that make us lose our voice, the critics. We can identify all of these things, yet they remain unpredictable as to what will trigger them and how intense they will be. These elements belong to the performing arts as well as to meteorology: shoals and the state of the currents are what determine a ship’s journey.

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 01

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 02

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 03

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 13

- Carnet de bord # 16 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 17 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 18 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 19 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 20 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 21 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 22 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 23 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 04

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 05

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 06

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 07

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 08

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 09

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 10

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 11

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 12

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 14

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 15

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 16

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 17

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 18

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 19

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 20

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 21

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 22

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 23

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 24