# 7 DOM JUAN OR THE FEAST WITH THE STATUE

By Jean Lambert-wild, Lorenzo Malaguerra and Marc Goldberg

The creative team behind DOM JUAN OR THE FEAST WITH THE STATUE share diary entries about their new show.

When we explore the play’s characters in some depth, we realise how absurd it would be to base our Dom Juan on Molière’s text only.

As we mentioned in the second diary entry, from the start we were aware that unlike Tartuffe or Alceste, Molière didn’t invent Dom Juan. Instead, he was tapping into a tradition that was relatively recent at the time, yet already rich (the “original” by Tirso de Molina had been published 35 years previously). The fate of the seducer of Seville had already been performed on Spanish, Italian and French stages. Of course, it is also later versions that come to mind, such as Mozart’s Don Giovanniand Pushkin’s The Stone Guest.

We noticed that, in Molière’s times, people were really fascinated by Dom Juan. This is then confirmed through the ages: after Spain, Italy and France, our hero conquered the English stage approximately ten years after Molière’s play, in a piece written by Thomas Shadwell: The Libertine, which Purcell would later write music for. Later, he returned to Italy with Goldoni, then moved to opera with Mozart in the following century. In the 19thcentury, he became a poetic inspiration for Byron, Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier, and a philosophical one for Kierkegaard. At the turn of the 20thcentury, we find him in classical music, first with Richard Strauss and then Sibelius, and then he is back in theatre in different versions by major authors such as Ödön von Horvath, Max Frisch or Montherlant. We find him in prose, with Apollinaire, after an unfinished project by Flaubert. From 1926, he is on screen, played by Errol Flynn and Johnny Depp. And this is without even mentioning the paintings by Fragonard, Delacroix and others…

Is he the same character each time? He is and he isn’t. He changes with the times. He inspires different great artists because he sheds light on a part of themselves or their contemporaries. In this way, he is not just a character but a myth: a theme that can be indefinitely revisited because it grows further and deeper every time it is explored anew.

We also progressively realised how unique Molière’s version was: in a way, it is a turning point, a reference on which future versions built up. Molière didn’t invent Dom Juan as a character but he greatly contributed to it becoming a myth. We have to own its uniqueness yet be inspired by the versions that came after, so that these layers can, for us, be a catalyst of freedom and discoveries.

Adapting and casting the play have been crucial moments for us to take ownership of it. But what do these suggest about how “our” Dom Juan could be?

In the first rehearsals, we took our intuition “literally”. Dom Juan coughs, spits out blood, staggers and seems to only become animated when he is seducing someone. Instead of death brutally interrupting the pleasure-seeker’s life in the form of a deus ex machinaCommander, the feast with the statue is the conclusion of a wild battle between the hero and an illness. This automatically gives the play a sombre quality.

A crepuscular veil falls on this story that authors and critics always struggle to define. Is it a comedy (according to Molière), a tragicomedy (according to his French predecessors), a dramatic poem (Pushkin), a play with special effects (according to many critics)? We tried everything to describe such an uncategorizable text. But it is certain that its tragic dimension (Shadwell for instance thought of The Libertineas a tragedy) was increasingly clear for us. This is what we’re interested in, as long as it doesn’t also obliterate the comic moments. We count on our Dom Juan’s clown-like dimension to find the right balance…

The constant threat of death has another consequence: it deepens the relationship between Dom Juan and Sganarelle. It pushes it in a direction that we decided to follow: the servant looks after his master, he caresfor him as much as he serves him. It is at times a maternal dimension that comes out of Steve Tientcheu, like the nurses of some Russian plays. His impressive build makes this dimension all the more theatrical.

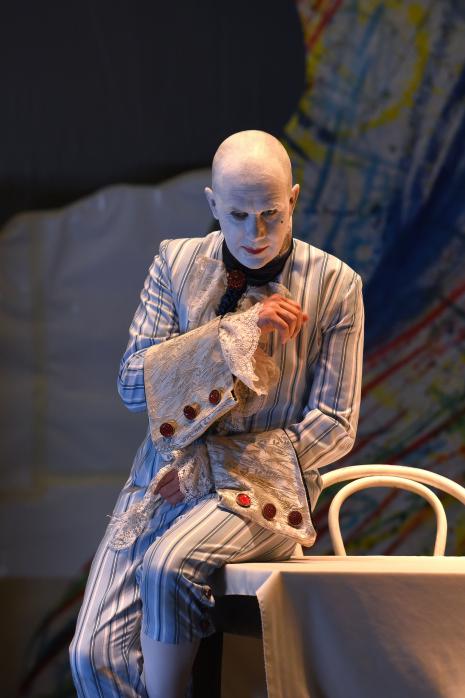

But something else happened on stage, which none of us had anticipated: Jean Lambert-wild’s sickly white clown now resembles Nosferatu. Is this a good thing?

We want to explore a vampiric dimension in Dom Juan, who feeds on women’s hearts to revive his vital energy. But then, we feel he looked more and more like Casanova, as a mechanical predator who belongs to Sade more than as a libertine. Of course, Dracula has an incontestable erotic dimension, made evidently clear by Polanski in The Fearless Vampire Killers. But Dracula’s hold over his prey comes from how he fascinates and terrorises them in a way akin to how an animal feels. Dom Juan on the other hand uses words to charm others, whether to seduce women, manipulate his father or Monsieur Dimanche, or convince Sganarelle or the Beggar. We realised then that we were superimposing two different myths and that they muddled our research.

This is probably because of how colours work together: for obvious contrast reasons, the vampire is pasty, with a pale face and a black cape, and on the lookout for blood, which is red. When Gramblanc, with a face entirely covered in make-up, walks up and down the stage looking for young flesh, he necessarily reminds us of a vampire, whose relationship todeath - as a creature who is immortal as long as it kills others, and to humans - as a predator, is very different from the sickly and charming Dom Juan we have in mind.

This is now the end of the second rehearsal period. We know a bit more about what we expect from our Dom Juan, but he resists us. In fact, we have made more progress on Sganarelle than on his master, because Jean Lambert-wild’s white clown creates some sort of short-circuit that we don’t yet know how to deal with.

We feel that we must refine Gramblanc so that he can play Dom Juan, not Nosferatu. Right now, and regardless of what Lorenzo Malaguerra suggests, the profound inter-connection between the clown and his costume invariably leads Jean Lambert-wild to play a vampire.

With this in mind, we part company. The months between now and the third rehearsal period will give Jean Lambert-wild, Lorenzo Malaguerra and Marc Goldberg an opportunity to discuss this. But we know we’ll have to wait until we’re back on stage to find Gramblanc’s Dom Juan.

- Carnet de bord # 1 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 2 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 3 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 4 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 5 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 6 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 7 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 8 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 9 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 10 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 11 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 12 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 13 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 14 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 15 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- Carnet de bord # 16 Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre

- # 5 DOM JUAN OR THE FEAST WITH THE STATUE

- # 7 DOM JUAN OR THE FEAST WITH THE STATUE